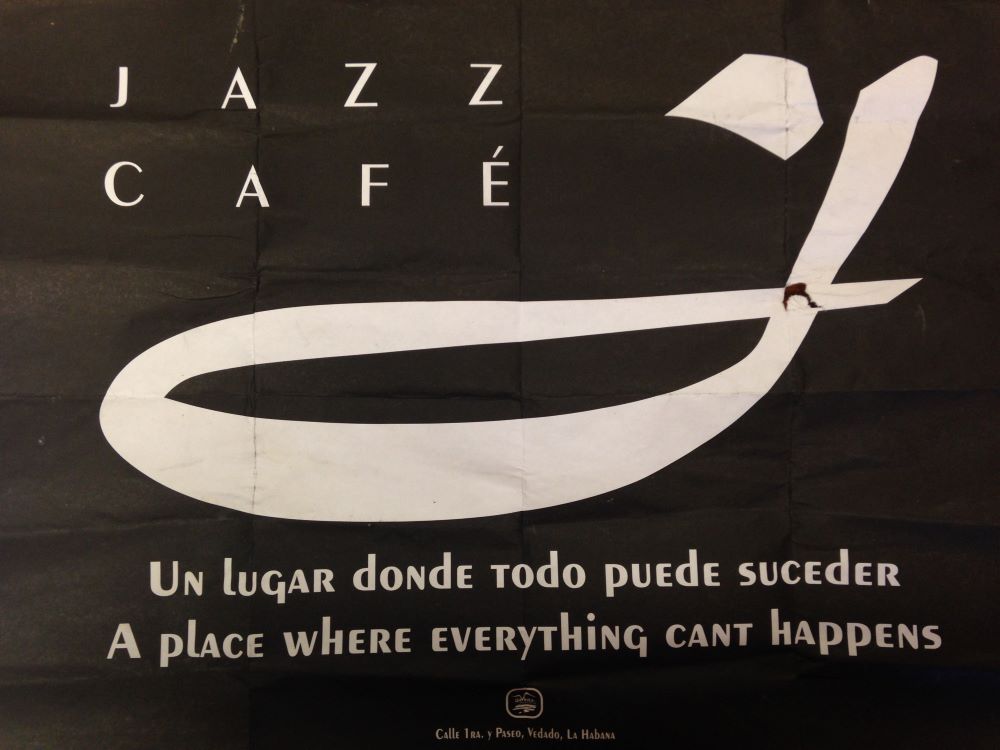

When visiting Havana’s once-premier nightclub “Jazz Café” in the early 2000s, one wondered whether the typo in the Jazz Café’s paper placemats was intentional or not. Correctly translated, the slogan “Un lugar donde todo puede suceder” should have read “A place where anything CAN HAPPEN.” Until the mid-2010s, Havana’s “Jazz Café” garnered cachet from its deliberate, English-language name and the fact that UNEAC, the government-run organization for writers and artists, subsidized its cost and the quality of menu items. Several nights a week, one could expect to see Cuba’s most famous actors, musicians and artists: they were not there to perform, but rather to simply hang out. At the time though, local Cubans were still legally barred from entering most nightclubs, hotels and other entertainment venues even when they had the money to afford it. Although never explicitly explained to the public, the Communist Party restricted access because they feared citizens would “harass” tourists and compete for cash with the state by free-lancing services (including sex work). According to most Cubans I knew, there was a more organic logic behind Cuba’s “tourist apartheid”: leaders like Fidel Castro did not want to let the Cuban people know just how inferior their own material existence was from that the one the socialist state created for foreigners. For all these reasons, perhaps the typo read less like a mistake and more like a parody. Havana, 2004.