Welcome to a treasure box of digitized documents, objects and imagery from UF’s Cuban archives at Smathers Libraries’ Special Collections! Here we present archival materials that span different periods of Cuban history and are also unknown to most historians and the public alike. We hope to inspire their use in classrooms around the world and to further knowledge of the rich political culture of Cuba. Gems of the Archive will itself become an archive as new examples are uploaded monthly.

All items curated by Lillian Guerra with the assistance of Miguel Torres Yunda.

- Cuca’s Cuban Christmas

Read more

Read moreIn December 1949, my great-grandmother “Cuca” threw a Christmas Eve party that featured one of the ultimate symbols of fashion and modernity at the time: a dazzling aluminum Christmas tree imported from the United States. Known as a generous and joyful host, Cuca (who rarely consented to any photographic documentation of her “aging process” after the age of 15), displayed that Christmas tree on an “advent altar”, flanked by a handmade image of the Holy Family in the manger on one side and of the Magi still en route to Bethlehem on the other.

- Chichi’s Christmas

Read more

Read moreLike the photograph that my maternal grandpa “Chichi” took of his three kids and his in-laws on Christmas Eve in December 1949, this image documents more than he probably intended about the social, economic, and cultural history of Cuba. At the center stands his ninety-plus-year-old mother, Teresa Rosado Rodríguez, known as “Mama Teresa,” holding the youngest member of the family, and his own mother, Carmen (in striped dress), the oldest of Mama Teresa’s 22 children.

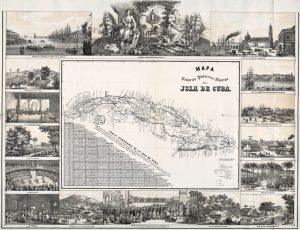

- Cuba’s Slave-Driven Economy & Map as Propaganda

Read more

Read moreProbably made in the late 1840s, this detailed map of Cuba features evidence of its “modern picturesque” advancement through historically sanitized scenes of commercial sugar and tobacco production that was— despite appearances to the contrary—made possible by hundreds of thousands of enslaved African and Cuban-born slaves.

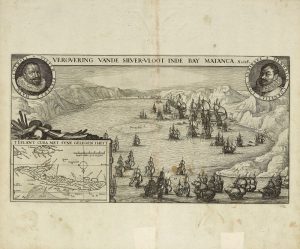

- 400-Year-Old Map of Matanzas Bay

Read more

Read morePrinted in Holland in 1628, this map shows a “birds-eye-view” of the port of the Bay of Matanzas made by cartographers who likely never visited either Cuba or the province of Matanzas themselves. Hence, they erroneously depicted the Bay of Matanzas (whose name commemorates the Spanish massacre of native people on the site) as a volcanic mountainous landscape.

- Ñica and My Family’s Story

Read more

Read moreWhen my dad fled Cuba for Spain in 1964, he left behind parents whom he never saw again: Agustín Guerra, an orphaned peasant who beat the odds to become a small tobacco farmer, and Aurora Almirall, a graduate of one of Cuba’s rigorous escuelas normalistas and a rural teacher who founded a one-room school in 1926.

- Ñica and the Reality of Race in Cuba

Read more

Read moreIn 1959, the most illiterate province in Cuba was not the most associated with foreign investors’ economic control or massive sugar plantations: it was Pinar del Rio, tobacco production’s legendary ground zero, where the belief that slavery and anti-Black racism has played little or no role in the region’s economic and social development continues to predominate. My own first reactions when I first visited its small rural towns and countryside reflected the resilience of such myths in my own family. Despite my father’s emotional and admiring stories about his family’s domestic servant, Ñica, he called her—every time she came up—not Ñica, but La Negra Ñica. As a very small child in my all-white world of Kansas, I once asked my mother if her first name was “Negra”. Her reaction—to silence me—was not unlike that of my Uncle Tiki, who recoiled in horror on my first visit to his house in the fall of 1996 and asked if she was still alive. No se dice eso aquí, nunca de Ñica o de nadie, he said. Deeply ashamed at the sudden realization of what I said and why it mattered, I remember trying to justify the epithet by explaining that my father ...

- Bodega Dreams

Read more

Read moreOnly the second son of eleven children to survive to adulthood (of twenty-two) born to María Teresa Rosado, my maternal grandfather Heriberto Rodríguez Rosado—better known in the family as “Chichi”—started selling mangoes on the streets of Cienfuegos with a goat named Alicia at the age of nine. That’s when Candido González, the Spanish-born owner of this small butcher shop and dry goods store on El Prado, the city’s main street, spotted his talent. Although Chichi had only the fourth-grade education that his older sisters and life on a small farm near Cumanayagua could offer, he was disciplined, ambitious and desperate to support his mom, younger brother and nine sisters. Chichi’s dad, a veteran officer in Cuba’s Liberating Army in the War of 1895-1898 against Spain, had just died of tuberculosis. Grateful to the Cuban Republic and not Spain for his business success, Candido presented Chichi with a deal: if he slept in the bodega overnight to serve as an alarm system in case of theft or fire, he could work and learn accounting from him during the day. He could also bring home a small salary, canned goods a month away from the date they would expire, and luxuries like ...

- A Cuban Family Celebrates the End of War

Read more

Read moreMarking the start of the Christmas holiday season of 1945, shortly after the end of World War II, this family photo speaks to a time in Cuba when electoral democracy had just ended the first of General Fulgencio Batista’s two regimes (1934-1944). Anything, for many Cubans, must have seemed possible. Those gathered include my ringleted, eight-year-old mother (second row from the front, eyes cast down) with her spectacled older brother Julián and mischievous younger brother Bertón as well as my grandma Yaya (flowered dress, third row) and grandpa Chichi (far right, same row). His joyful expression and toothy grin are hard to ignore. Yet this family had struggled among themselves for mutual acceptance. Marriages that crossed intense, political and historic class divides had haltingly united them, with some (like Chichi) representing impoverished peasantries and others, like abuela Yaya hailing from ancient, slave-owning colonial clans like the Sotolongo and Suárez del Villar families. From the 1860s-1890s, the latter’s wealth had steadily eroded as abolition took effect. The three wars that Cubans, such as Chichi’s dad, fought to liberate Cuba from Spain had also created demands for a just, capitalist economy, an end to racial discrimination, and a sovereign state. Still, amidst ...

- Escuelas Básicas de Instrucción Revolucionaria

Read more

Read moreLaunched for a three-year run in 1962, “Basic Schools of Revolutionary Instruction” were designed to teach the principles of Marxist-Leninism to legions of Cuban workers who were enthusiastic supporters of Fidel Castro’s Revolution but knew next to nothing about Communism—including how or even why the government was supposed to own and plan the national economy. Hoping to boost productivity among all workers, officials relied on the EIBRs to develop cuadros (awkwardly translated from the Soviet word “cadre”).

- Cantando a Camilo [Singing to Camilo]

![Cantando a Camilo [Singing to Camilo]](https://cubanstudies.history.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/173/2-Cantando-EBIR-Resized-239x300.jpg) Read more

Read moreFlanked by fellow instructors at an Escuela Básica de Instrucción Revolucionaria, Roberto García Añel, a young twenty-something who worked in the accounting division of his factory, led worker-students in revolutionary songs at this class session, held sometime in 1964. On the wall hangs a mass-produced portrait of the popular revolutionary Comandante Camilo Cienfuegos, whose plane had mysteriously disappeared over the sea in late October 1959, to the horror of millions of Cubans and the suspicion of many. The use of songs (such as Canto a Camilo) as a method of indoctrination and instruction abounded in these schools, as did reliance on slogans to explain Marxism or government policies. Songs and slogans served as substitutes for rigorous reading assignments, tests, and discussions of Marxism because the majority of worker-pupils attending EBIRs had not even completed the sixth grade. Party critics of these methods—considered mostly a vehicle for encouraging loyalism among the already loyal–called the approach manualismo and a waste of time. One wonders what the participants at the time thought. Havana, 1964. Personal Collection of Rolando García Milián, used with permission.

- Revolutionaries first, Marxists last?

Read more

Read moreIt is impossible to know whether young loyalists like EBIR teacher Roberto García Añel would have chosen a Marxist path for Cuba if Fidel Castro had given them a choice. What is clear is that García Añel made a commitment to what he understood was “the Revolution” as a very young man, and he worked hard to promote the ideology that Fidel promised would be Cuba’s salvation. Posed once again with their training manuals, the faces of these young “revolutionaries” and the fact that García Añel saved these photographs for so long help humanize Cuba’s experience—especially in the early 1960s when nobody, especially the very young, could have predicted what would happen in the decades to come. A three-pack-a-day cigarette smoker, García Añel died at the age of 42 in 1981. Havana, 1964. Personal Collection of Rolando García Milián, used with permission.

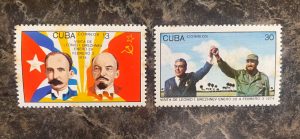

- Stamps: The Revolution’s Stained Glass

Read more

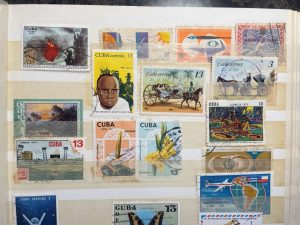

Read moreStamp collecting reached a zenith of popularity in Cuba and the United States about the same time: 1950s and 1960s. As Cuba’s revolutionary state adopted communism, government organizations charged with ideologically educating citizens heavily promoted the hobby as a methodical, non-lucrative and meditative way to broaden one’s consciousness.

- Camilo and continuity

Read more

Read moreThe popularity of the handsome (and almost always smiling) Comandante Camilo Cienfuegos rivaled that of Fidel Castro until late October 1959 when the airplane meant to fly him back from Camagüey to Havana mysteriously disappeared over open water. Only a few hours earlier, he had reluctantly arrested fellow Comandante Huber Matos for resigning his post to protest the elevation of secret communists to important positions in the Rebel Army. Matos went on to serve twenty years in prison while “Camilo” became a malleable myth and martyr for the state. Dated 1968-1970, stamps made him an icon of Cuba’s allegedly uninterrupted century of revolution and the progenitor of the Camilitos, cadets at one of Cuba’s elite communist military academies. Eduardo “Guayo” Hernández Collection, Smathers Libraries, University of Florida

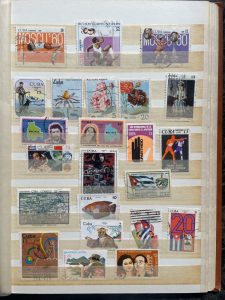

- Your spies are our heroes

Read more

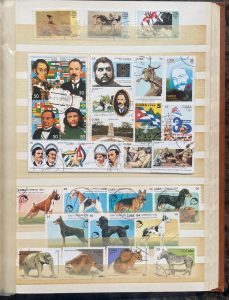

Read moreA dizzying array of commemorations covers this page of stamps in Abreu Hernández’s album. While top designs honor flora, fauna, art, cinema, and the Moscow Summer Olympics of 1980 (boycotted by much of the Western world), other stamps depict guerilla leader Ernesto “Che” Guevara, as well as Tania Bunke, his lover and East German spy, whom a US-trained unit had recently executed in Bolivia. Also featured are Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, Communist Party members convicted and executed by the United States in 1953 for passing information on the atomic bomb to the Soviet Union. Eduardo “Guayo” Hernández Collection, Smathers Libraries, University of Florida

- African solidarity…and the enslaved

Read more

Read moreA close-up of stamps reveals Cuba’s intense claims to solidarity with the world’s anti-colonial liberation movements in Africa and Vietnam and the Soviet Union’s victory over fascism in World War II. Yet contradictions persisted. One stamp honors Amilcar Cabral, a Marxist intellectual who launched independence in the Portuguese colony of “Guinea” (now Guinea Bissau) and argued for the “re-Africanization” of pride and culture. Alongside, another stamp unironically celebrates “The Day of the Stamp” with a depiction of women from Cuba’s sugar planter elite out for a ride in an open-air carriage driven by a calesero, one of Havana’s legendarily well-dressed slaves. Eduardo “Guayo” Hernández Collection, Smathers Libraries, University of Florida

- Fidel’s Bulls & Cows

Read more

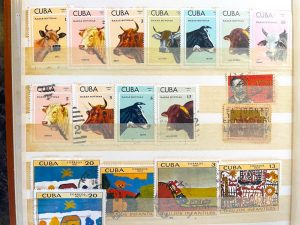

Read moreIn the mid-1960s through the early 1970s, Fidel Castro created (and personally managed) a national crossbreeding and insemination program that most scholarly observers credit with the destruction of Cuba’s vast herds of beef and dairy cattle. Confiscated from their owners—both wealthy, middle-income, and poor alike between 1960-1962—Cuba’s cattle died or failed to produce enough milk to cover national needs as early as 1964. From that year to the present, access to dairy milk has been permanently rationed and available to only very small children. Yet, in the 1970s and 80s, when the failure of Fidel’s cattle experiments reached a head, and Soviet imports of canned and powdered milk began to flow, government publicity agents portrayed the opposite reality: stamps depicted an array of healthy, diverse breeds. Later, the Ministry of Agriculture would erect a monument to F1, a cow named Ubre Blanca , which produced almost 29 gallons a day! Eduardo “Guayo” Hernández Collection, Smathers Libraries, University of Florida

- Cubanizing Abe Lincoln

Read more

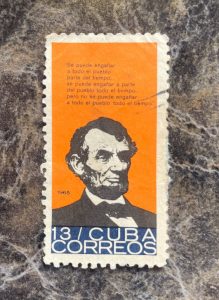

Read more“You can fool all of the people some of the time and some of the people all of the time, but you cannot fool all of the people all of the time.” This famous quote, attributed to US President Lincoln, occupied an unlikely place in 1960s Cuba: unanimity—the opposite of pluralism, let alone democracy–had been an officially required condition for inclusion in the Revolution since at least 1961. Communist Party censors might have ascribed irony to the “foolishness” of those who believed in the United States’ democracy, but its applicability to Cuba’s Communist dictatorship was also deeply ironic. Eduardo “Guayo” Hernández Collection, Smathers Libraries, University of Florida

- Prehistoric Humans & the Birth of Ho Chi Minh

Read more

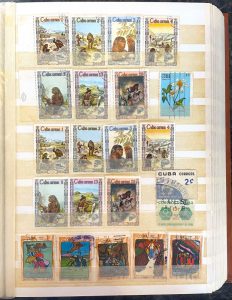

Read moreIssued at the same time (1970), these stamps depicting the evolution of humans and the “eightieth anniversary” of the birth of Vietnam’s liberator diverge radically in their illustrators’ style. Yet they are deeply didactic and precise in the lessons they convey. Eduardo “Guayo” Hernández Collection, Smathers Libraries, University of Florida

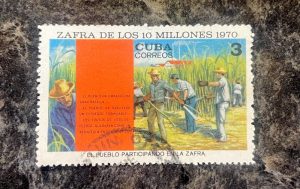

- The Ten Million Ton Harvest of 1970

Read more

Read moreCalled by Fidel Castro to be the largest sugar harvest in Cuban history and carried out by a nationwide force of nearly half a million unpaid (“volunteer”) workers, the Ten Million Ton Harvest of 1970 brought Cuba’s economic development to a grinding halt. Although they produced eight million tons—a historic record, the human cost workers paid demoralized them for years to come. Nonetheless, this stamp claimed the opposite: “The people have unleashed a great battle… The people have realized a formidable effort. …The fruits of this effort shall stand as an historic achievement.” Eduardo “Guayo” Hernández Collection, Smathers Libraries, University of Florida

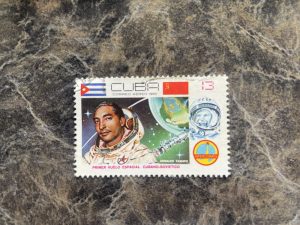

- The Soviet Orbit

Read more

Read moreThanks to the Soviet Union, Cuba enjoyed a short-lived “space program” that launched pilot Arnaldo Tamayo into space alongside Soviet cosmonaut Yury Romanenko in September 1980. Eduardo “Guayo” Hernández Collection, Smathers Libraries, University of Florida

- Special Period Stamps

Read more

Read moreWith the disappearance of Soviet aid and the Soviet Union itself by 1993, Cuba’s mail service ground to a virtual halt. Yet stamps continued to be produced even though the island’s mail carriers were in short supply. These years, known by Fidel Castro’s moniker as “The special period in a time of peace,” coincided historically with the centenary of Cuba’s final war for independence and the deaths of many of its heroes, including Antonio Maceo, a three-war veteran general who had openly fought for racial equality—rather the mere “racial harmony” endorsed by his peers. Here, Maceo’s prominence is superseded by other Latin American liberators. The Nineties also produced a series featuring pedigree dogs, undoubtedly the least likely icon one might associate with post-Soviet but still Communist-led Cuba. Eduardo “Guayo” Hernández Collection, Smathers Libraries, University of Florida

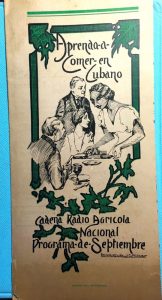

- “Learn to Eat in Cuban”

Read more

Read moreAprender a comer en cubano was literally the name of a daily, national public radio program sponsored in the 1940s by the first elected government of the Auténtico Party. Its leaders claimed to represent the “authentic” program of Cuba’s 1895 War for Independence. The least fulfilled goal of this war and the Republic it founded was the establishment of a prosperous small farmers’ economy.

- “Revolutionarily Yours”

Read more

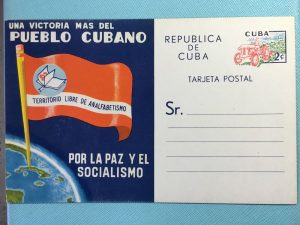

Read moreThe Cuban government printed postcards like this one as well as special stationery for Cuban volunteer teachers who participated in the 1961 Literacy Campaign. As former maestro voluntario Ernesto Chávez explained to his students, citizens were supposed to sign off their letters and notes, much as adherents of the state still do, “revolucionariamente” as a public testament to their loyalty. Decorated with the slogans Yet Another Victory for the Cuban people, Territory Free of Illiteracy and For Peace and Socialism, the postcards deflected criticism and fear generated by the government’s recent takeover of the press, the ending of elections and official demonization of not only opposition to government ownership, but of doubt in its success. When they received such mail, readers were supposed to become supporters of the “Cuban Revolution” without feeling that they were endorsing Marxism, Communism or even Cuba’s alliance with the Soviet Union. Conceived by top militants of Cuba’s Communist Party (still known as the PSP or Partido Socialista Popular until 1965), the tactic had a long, successful afterlife, especially among the United States’ younger generations who considered themselves the “New Left”. The latter also echoed another PSP-crafted strategy: the related idea that Cuba had ...

- Ideological Training Songs for Voluntary Teachers

Read more

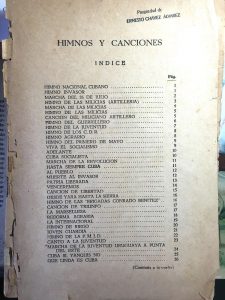

Read moreThis list of songs come from a teacher-training manual that Ernesto Chávez carried like a socialist Bible when he served for four years as a maestro voluntario in the mountains of El Escambray and Oriente province (1960-1964).

Read more "Ideological Training Songs for Voluntary Teachers"

- Mementos of a Euphoric Youth

Read more

Read moreSome of the strongest memories we conserve are embedded in the fragile tokens of a striking experience we once felt deeply but can no longer fully describe. Ernesto Chávez conserved these ribbons for decades. Raggedy from pinning it to the front of his teacher’s olive-green uniform nearly every day in 1960, one ribbon reads Patria o Muerte .

- ID Card of the Committee for the Defense of the Revolution

Read more

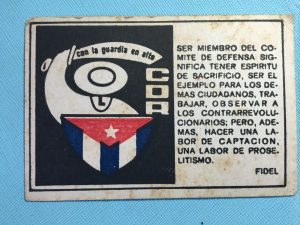

Read moreThis card, commonly called a carnet in Cuba, belonged to the mother of Ernesto Chávez. She joined her local Comité de Defensa de la Revolución means having a spirit of sacrifice, being an example to ...

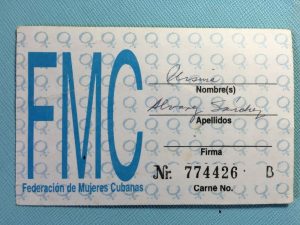

- ID Card of the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC)

Read more

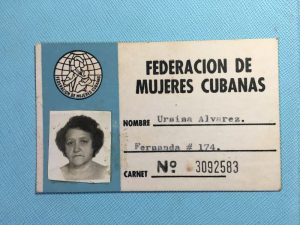

Read moreSince the 1960s, many scholars have noted how Cuba’s virtually all-male leadership burdened women with the most work “for the Revolution” yet they enjoyed little power over policies not immediately relevant to their gender. Women were expected to fulfill domestic chores, stand in line for rations, work outside the home, volunteer for no pay and, of course, look “feminine”, that is, keep up the standards of beauty promoted in the government press for the benefit of men. Consistent with these expectations, the emblem for the FMC shows a woman dressed in militia uniform, carrying a weapon in one arm and a baby with the other. With the weight of the globe behind her, she has no free hand. Ernesto Chávez Collection, University of Florida.

- Cuba’s FMC: A Cost-Benefit Analysis

Read more

Read moreDirected for decades by Vilma Espín, the FMC was the “mass organization” in which all women were supposed to participate. The term itself connotes Cuba’s adoption of norms from the Communist bloc.

- Ernesto Chávez and Lillian Guerra in 2016

Read more

Read moreThe University of Florida remains grateful to Ernesto Chávez for the donation of his personal archive, papers, books, and memories of life in early revolutionary Cuba for researchers and future generations. A memoirist and scholar of peasant and Canary Islanders’ folk traditions, Ernesto Chávez lives in Cuba. A guide to its contents can be found here.

- BBC Archive: Robin Day in Castro’s Cuba

Read more

Read moreFor this edition, we invite you to see a gem from the BBC Archive, which transports us back to the struggles, questions, and drama of Cuba’s early years of revolution.

Cover Image: Revolutionaries listen to Fidel Castro’s weekly televised show, March 1960. Andrew St. George Collection, University of Florida.