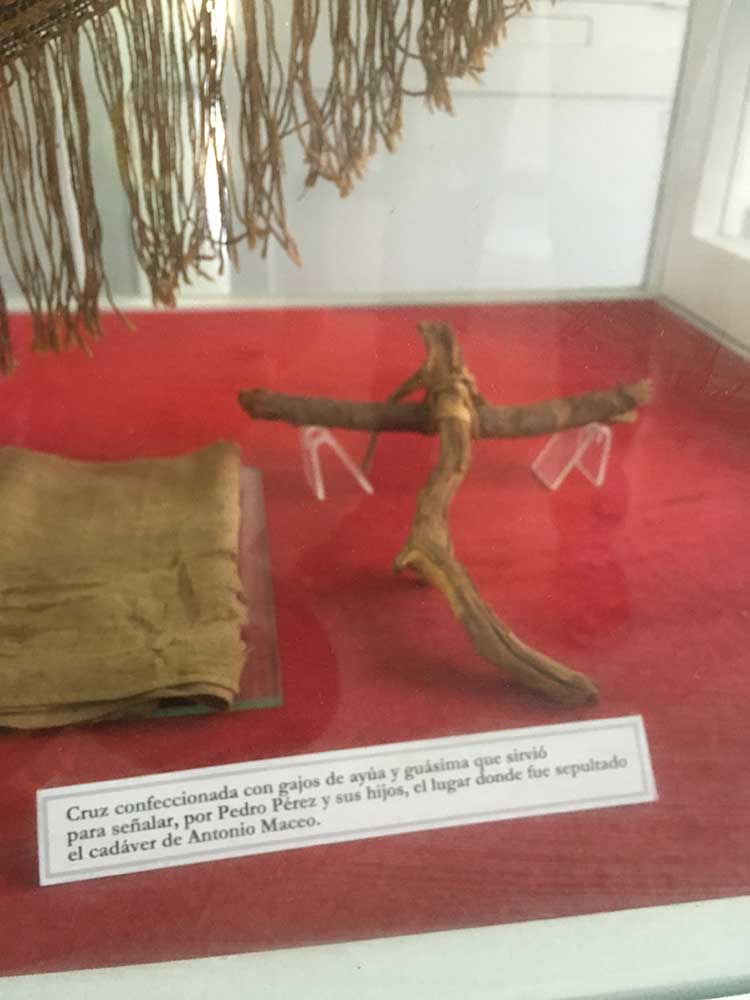

At the end of Cuba’s third war for independence, when the United States’ military intervention and occupation ended patriots’ dream of national sovereignty, Emilio Bacardí forged a clear path of redemption by doing what few of his class peers even considered: he began scouring the countryside for the personal possessions and relics of Cuba’s black and white liberators, such as Antonio Maceo’s handwoven, sheer hammock, silken stockings made by his wife, and his the small handmade cross that had once marked Maceo’s grave. Bacardí also sought out the secret grave of patriot Carlos Manuel de Cespedes, the planter who launched Cuba’s first war for independence when he freed his slaves on 10 October 1868, called them “citizens” and urged them to fight for the freedom of Cuba as their own. Whenever Cuban heroes died in battle, the Spanish ordered them buried in common graves—if they could find them. In the case of Maceo, a small handmade cross marked the site of his body, seen here. Emilio Bacardí also rescued from oblivion the extraordinary sarcophagus that had protected the loss of his body in a common grave until 1910. Céspedes’s soldiers had painstakingly smelted it together from more than 600 iron bullets and shell casings.