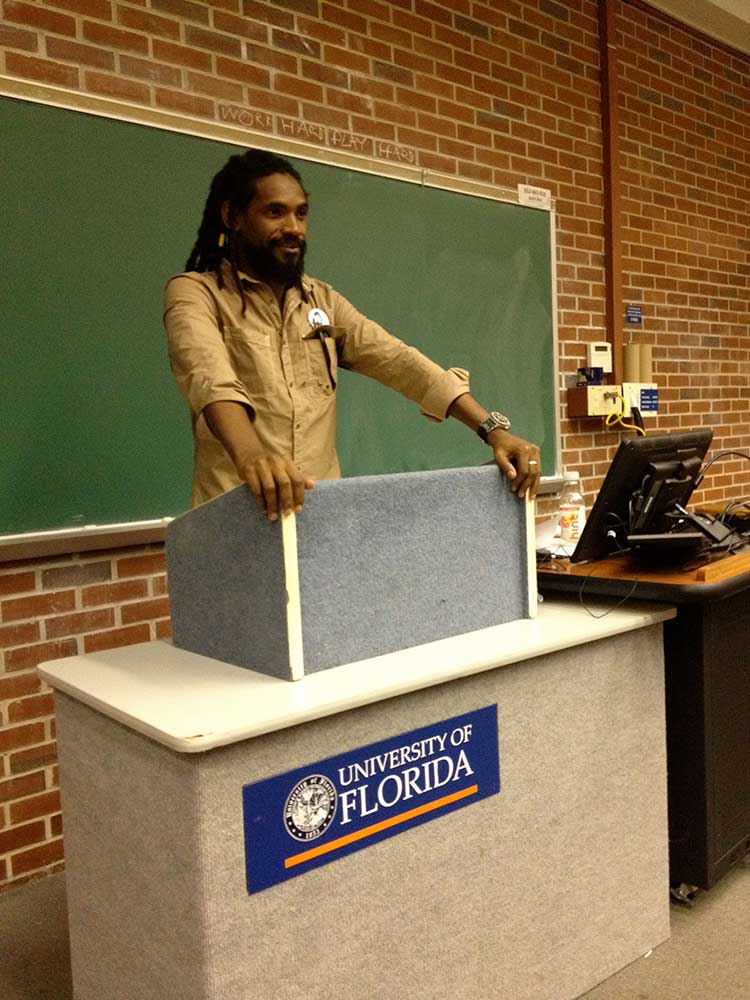

Since the mid-1990s, Black Cuban musicians had begun re-engineering the African American genre of hip-hop and rap in ways no-one expected. In contrast with earlier generations of musicians who performed and recorded during the first three decades of Communist rule, rap artists in the 1990s benefitted from a Special Period reform that allowed artists to produce, market and sell their creative products (in this case music) independently of the state. For Raudel and other pioneers of Cuban rap such as Soandres Del Río Ferrer (who also visited Prof. Guerra’s class a year earlier), this meant that they could shirk Communist censors and tell the world about the deep anti-Black racism that flourished among Cuba’s government institutions, police and average citizens, despite claims to the contrary. Thanks to President Obama’s policy openings, UF students like Ashley Mayor got to discuss Black Cuban rap and the lyrics of Raudel’s songs “live and in person”.