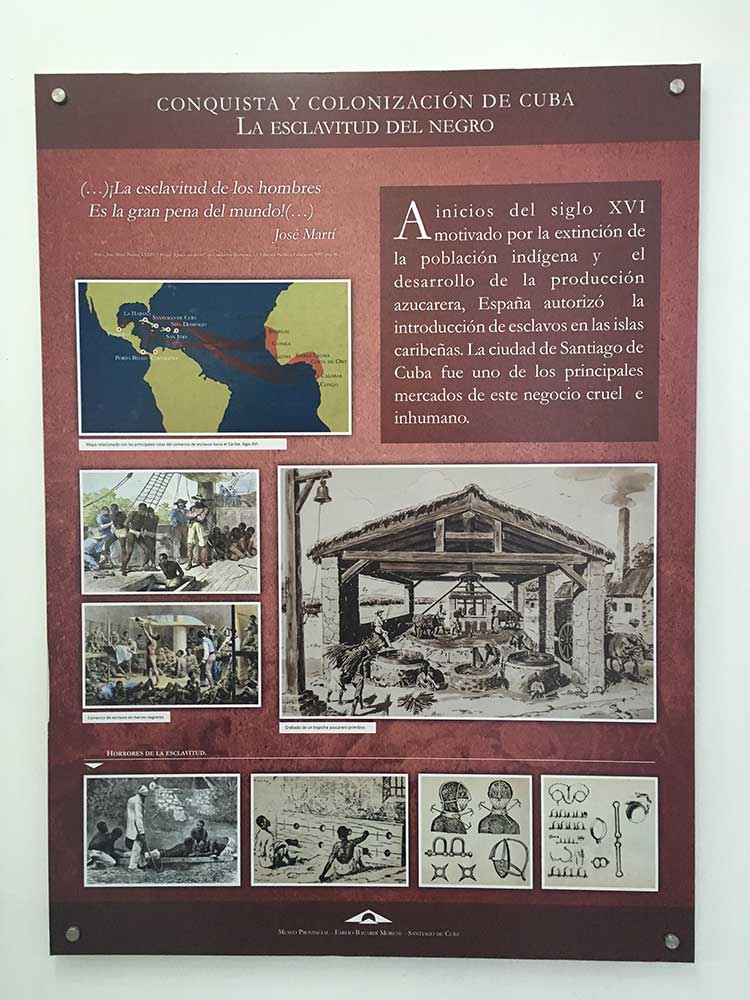

One of the most striking aspects of Havana’s most important colonial era museums and memory markers is the shocking erasure of slavery and the enslaved from virtually all narratives, displays and exhibits. Indeed, unless one counts the racial mockery of the blackface dolls sold at tourist sites or the costumes worn by employees of the Historian of the City in the Special Period, references to non-whites are hard to find in the public history of almost all Western Cuba. (Only Matanzas’ Museum of the Slave Trade is an hard-fought exception.) By contrast, museums, plaques, and landmarks in Santiago de Cuba focus on Black Cubans’ fight for abolition, nation and racial equality. In particular, the Bacardí Museum launches its national narratives of identity in the history of indigenous resistance to the Spanish, slavery and dramatic evidence of the state-sanctioned and planters’ violence that defined enslaved people’s experiences. Objects include the axe used to execute slave rebels in the central plaza of Santiago de Cuba for more than a hundred years, shown alongside a centuries-old lithograph documenting its use. Stocks, manacles and other torture devices accompany detailed accounts of slavery’s essential role in sugar production. The acceptability of violence emerges amidst visitors’ growing consciousness of the necessity of its invisibility: after all, only Cubans had the saying, Sugar is made with blood. European and American consumers did not. Santiago de Cuba, July 2016.