Welcome to a treasure box of digitized documents, objects and imagery from UF’s Cuban archives at Smathers Libraries’ Special Collections! Here we present archival materials that span different periods of Cuban history and are also unknown to most historians and the public alike. We hope to inspire their use in classrooms around the world and to further knowledge of the rich political culture of Cuba. Gems of the Archive will itself become an archive as new examples are uploaded monthly.

All items curated by Lillian Guerra with the assistance of Miguel Torres Yunda.

- What did Fidel Castro want?

Read more

Read moreThese editorials were all published around the time of Fidel Castro’s April 1959 “good will” speaking tour of the eastern seaboard of the United States. Together, they reflect a capsule history of how differently Americans were reacting to the spectacle of Fidel as well as the meaning of the Revolution itself across the country.

- “The Real History Behind Fidel Castro’s Revolution: How Cuba Lost Its Freedom”

Read more

Read moreCreated by Deutsche Welle (DW), Germany’s public service and international broadcaster, this is an educational video on the history of Cuba, Fidel Castro, the Cuban Revolution, and the aftermath of repression, economic upheaval, and lost revolutionary hope.

Read more "“The Real History Behind Fidel Castro’s Revolution: How Cuba Lost Its Freedom”"

- Nancy Macaulay, 2016

Read more

Read moreIn 2012-2014, Nancy Macaulay made a gift of the photographs, artefacts, letters, and documents that she and her husband, Neill Macaulay, had preserved from their years of participating in Cuba’s war against the dictator Fulgencio Batista and the first two years of the Cuban Revolution, 1959-1960.

- Letters from Lucille

Read more

Read moreIn the summer of 1962, one of Nancy and Neill Macaulay’s former neighbors, Lucille, wrote them a series of letters chronicling the increasing struggle of daily life in Cuba. A Free Will Baptist missionary, Lucille, was committed to staying in Cuba, despite increasing hardships.

- View from the Epicenter: Prensa Latina’s Photographs of the Cuban Missile Crisis

Read more

Read morePhotographers from Cuba’s wire service, Prensa Latina, took hundreds of pictures of Cubans across the island during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Most photographs in historical coverage of the missile crisis feature Fidel Castro, but this collection shows the variety of ways that everyday men, women, and children participated in the crisis, from manning anti-aircraft weapons, to keeping the factories humming, to gathering at the airport to welcome foreign dignitaries like Anastas Mikoyan.

Read more "View from the Epicenter: Prensa Latina’s Photographs of the Cuban Missile Crisis"

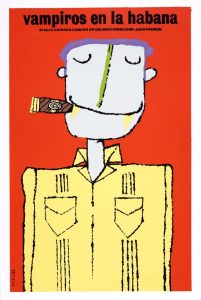

- Vampiros en la Habana / Vampires in Havana (1985)

Read more

Read morePart of a fully digitized collection, this poster promoted the first of a two-part series of animated movies directed by Juan Padrón and produced by Cuba’s government film industry, known by the acronym ICAIC. Both Vampiros en la Habana and its 2004 sequel ¡Más Vampiros en la Habana! proved wildly popular among Cuban citizens.

Read more "Vampiros en la Habana / Vampires in Havana (1985)"

- El Hombre Agradecido / The Grateful Man (1991)

Read more

Read moreCrafted to parody a classic Cuban rum label, this poster for the animated short El Hombre Agradecido, directed by Tulio Raggi and produced by Cuba’s government film industry (ICAIC) also serves as a metaphor for the film’s storyline: a man rescues an oblivious, perpetual drunk from being run over by oncoming traffic at a Havana intersection only to fall victim to the man’s (literally) toxic form of alcohol-laced masculinity. Darkly humorous, …

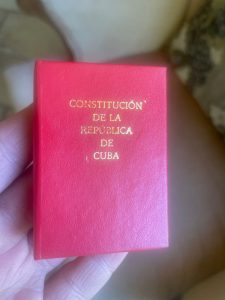

- Cuba’s Little Red Book

Read more

Read moreIn 1986, militants of the Communist Party received a miniature version of Cuba’s first Party-authored Constitution. More than just a memento to mark the tenth anniversary of its ratification, the mini-Constitution was supposed to be kept in a pocket or purse so “revolutionaries” could better defend the government’s policies and Communist ideals whenever they encountered complaints or rebukes at the workplace or on public streets.

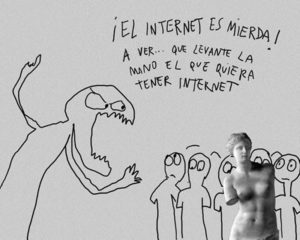

- “Galería Imeil” of artist Lázaro Saavedra

Read more

Read moreIn the early 2000s, Lázaro Saavedra, one of Cuba’s most renown artists, used his Cuban government email as a digital “gallery” for sharing political cartoons and other visual commentaries. Most were bitingly funny critiques of government policies found nowhere else. Here, Saavedra’s “monster” admonishes armless citizens, saying: The internet is crap! Let’s see….whoever wants internet raise your hand!” (Personal email from the artist, 2007)

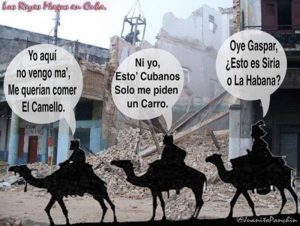

- “The Three Kings in Cuba” by Juanito Panchín

Read more

Read morePosted widely on Cubans’ (then illegal) social media accounts, this “postcard” by island humorist Juanito Panchín depicts the messiah-seeking Three Kings of the Christian Bible traversing Belascoín, a main thoroughfare in Havana lined with rubble from collapsed buildings. Their wry comments comparing war-torn Syria to normal life in post-Soviet Cuba islanders considered hilarious: —I ain’t coming here no more. They wanted to eat my camel. —Me neither. These Cubans only ask me for a car. —Hey, Gaspar: Is this Syria or Havana? (Public post and email collection of Lillian Guerra, 2008)

- College Students-Turned-Guerrillas

Read more

Read moreThese two young University of Havana students were most likely quemados, “burnt out” survivors of multiple confrontations with Batista’s police and security services, whose escape from Havana’s daily dangers in the late 1950s leaders of the revolutionary opposition authorized in order to save their lives and to reward them for their brave service.

- Original “Latin Lover” Meets Fidel

Read more

Read moreA three-decade veteran diplomat of the Dominican Republic’s dictator Rafael Trujillo, Porfirio Rubirosa was famous for his lavish lifestyle and five marriages. His wives included Trujillo’s daughter Flor de Oro (“Flower of Gold”), two actresses, and two American heiresses who also happened to be the richest women in the world at the time, Doris Duke and Barbara Hutton. No doubt justified by his diplomatic role, Rubirosa’s decision to drop by a celebratory cocktail reception at the Presidential Palace in early 1959 surely caught revolutionaries by surprise, including an awkwardly framed Fidel Castro. Havana, January 1959. Andrew St. George Collection, Smathers Library, University of Florida.

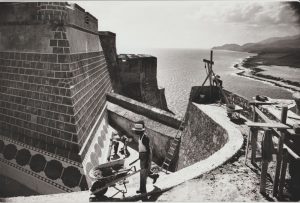

- Restoring El Morro, Santiago de Cuba

Read more

Read moreLike previous “populist” governments of the Cuban Republic before the Revolution of January 1959, the new regime under the leadership of the 26th of July Movement quickly expanded employment opportunities through public works. Here, the Spanish colonial fortress in Santiago, known as the Castillo de San Pedro de la Roca, gets a much-needed facelift. Santiago de Cuba, 1960. Andrew St. George Collection, University of Florida.

- Cuba’s Labor Movement Loses Autonomy

Read more

Read moreIn building an authoritarian state, control over a country’s labor movement is as important, if not more so, as control over the press and the willingness of citizens to criticize. This was especially true in Cuba after 1959 when the Confederación de Trabajadores de Cuba committed to a “no-strike” policy in order to help stabilize the economy and promote industrial growth for the benefit of all Cubans. However, over the course of 1960, leaders of the revolutionary government, especially Fidel Castro, increasingly began to insist that any criticism of its leadership or contestation of policies constituted an invitation for the United States to invade, intervene, or subvert the state. As a result, the CTC began to further violate its own rules out of solidarity with Cuban sovereignty: here, elected leaders appeared not in the working-class attire of civilians but as militiamen, armed and at the service of Fidel Castro’s state-directed vision of change. Havana, March 1960. Andrew St. George Collection, Smathers Library, University of Florida.

- Nationalization of Cuba’s Oil Refineries

Read more

Read moreIn late June 1960, journalist Andrew St. George snapped this picture of Cuban militiamen preventing the managers of US-owned oil refineries from entering the gates of the plant. Far from chaotic, the scene exemplified the orderly plan by which Prime Minister Fidel Castro achieved a major standoff with the United States and then precipitously imposed a radicalization of economic policy in defense of Cuban national sovereignty. Fidel Castro’s orderly plan began when the Soviet Union offered to sell Cuba crude oil at a much cheaper price than US producers. After foreign-owned oil refineries on the island refused to process Soviet crude, Fidel Castro moved quickly to decree a government takeover of these properties. The move was strategic, perfectly designed to enrage US officials and thereby trigger the United States to unilaterally cancel the purchase of Cuba’s upcoming sugar harvest and suspend trade in a tidal wave of retribution. Both moves would have devastated Cuba economically. Yet, US hostility served a purpose central to further empowering Fidel Castro and supporters of an authoritarian state: it allowed the Soviet Union to save Cuba from the brink of destruction. Immediately after the US cancelled its sugar deal, the Soviets promised to purchase not ...

- The Desk of José Martí

Read more

Read moreThis mammoth mahogany desk stands in the childhood home of Cuba’s premier nationalist leader of the 1880s and 1890s, José Martí, as a witness to his enduring literary brilliance and indefatigable activism on behalf of Cuban Independence from Spain.

- National Monument to José Martí

Read more

Read moreOne decade ago, in 2015, UF Dean of Libraries, Judith Russell, achieved an unprecedented and transformational agreement with Cuba’s Biblioteca Nacional de Cuba “José Martí” for the mutual exchange, cataloguing and digital conservation of rare, unique and previously inaccessible documents, newspapers, books and other materials for researchers at the University of Florida and the international community at large. On the heels of a successful consultation with local librarians, we visited the massive national monument honoring José Martí, which was built to commemorate the centennial anniversary of his birth in 1953.

- Landing of José Martí in Cuba for 1895 War

Read more

Read moreOn February 24, 1895, José Martí and General Máximo Gómez, the commander-in-chief of revolutionary armed forces,

issued the Grito de Baire from Baire, a village near Santiago, proclaiming a call to arms for Cuba’s last independence war. Martí and Gómez traveled together from exile to join the troops a few weeks later, landing on the still isolated and unassuming “little beach of Cajobabo” in far-eastern Cuba. On the beach itself, a giant stone monument, erected during the Republic (1902-1958) commemorates their lifelong sacrifices and those of other patriots of the war.

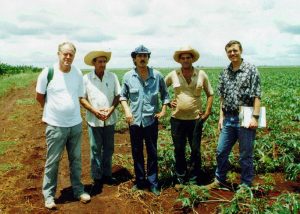

- UF-IFAS and University of Havana faculty in the field

Read more

Read moreUniversity of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Science (UF/IFAS) faculty and University of Havana collaborators visit a potato farm in Havana Province (1995). The gentleman in sunglasses in the center of the photo is UF/IFAS Professor Dr. Jose Alvarez, who envisioned the possibility of active, nonpolitical, collaboration between U.S. and Cuban scientists and who was instrumental in bringing the University of Florida/University of Havana collaboration on agricultural issues to fruition.

Read more "UF-IFAS and University of Havana faculty in the field"

- UF-IFAS researcher Dr. Fred Royce conducting field research in Cuba

Read more

Read moreUF/IFAS Dr. Frederick Royce (right) when he was conducting graduate field research in Cuba in 1996. Also in the photo is Dr. Brian Pollitt (Univ of Glasgow, left) and cooperative vice-president Victor Franco (center) at sugarcane production cooperative (CPA) “Revolución de Etiopía,” Ciego de Avila Province, Cuba. Dr. Royce’s thesis “Cooperative agricultural operations management on a Cuban sugarcane farm: ‘…and everything gets done anyway’ ” was based on truly unique, extensive field research conducted on Cuban sugarcane cooperatives, and he has been a key and essential member of the University of Florida/IFAS-University of Havana collaborative research project on agriculture and natural resource issues. Photograph by Fred Royce. Guest curators Fred Royce and William Messina.

Read more "UF-IFAS researcher Dr. Fred Royce conducting field research in Cuba"

- Cuba citrus juice processing plant

Read more

Read moreUniversity of Florida/IFAS and University of Havana faculty prepare to tour the Cuban citrus processing facility in Jagüey Grande, Matanzas Province, Cuba, along with facility staff and administrators (2000). Photograph by Fred Royce. Guest curators Fred Royce and William Messina.

- UF-IFAS faculty meeting members of Cuban agricultural production cooperative

Read more

Read moreUniversity of Florida/IFAS faculty attend a meeting of members of the Cuban citrus agricultural production cooperative “30 de Noviembre”, Artemisa Province (2002). Photograph by Fred Royce. Guest curators Fred Royce and William Messina.

Read more "UF-IFAS faculty meeting members of Cuban agricultural production cooperative"

- Florida citrus industry representatives tour Cuban citrus grove

Read more

Read moreFlorida citrus industry representatives and UF/IFAS faculty members visit citrus groves of Citricos Ceiba farm near Caimito, Artemisa Province, Cuba, 2003. By the early 1990s, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the loss of Cuba’s preferential trade arrangements, the citrus groves of the Citricos Ceiba state farm had fallen into neglect. Agricultural inputs were largely unavailable, vines covered the trees, tall weeds surrounded them and citrus production was very low. In February of 1994, the “9 de Abril” UBPC cooperative was established, becoming one of 6 such cooperatives on what were formerly state-managed lands of the Citricos Ceiba state farm. With more control over the land, the budget, and especially the management of work, the cooperative instituted a new management system in their citrus groves. By early 2003, the cooperative had 496 members, up from the initial 150 in 1994. The productivity of the principal crop, grapefruit, increased from 13 mt/ha during the 1993-94 harvest to 39.6 mt/ha in 2003-04, which was close to Florida’s average grapefruit yield that season. Photograph by Fred Royce. Guest curators Fred Royce and William Messina.

Read more "Florida citrus industry representatives tour Cuban citrus grove"

- New incentive-based management system in Cuban citrus

Read more

Read moreThe new incentive-based management system used throughout Cuba’s Citricos Ceiba agricultural production cooperatives is based on a “finca” of around 15 hectares of citrus. The maintenance of the trees in each finca is overseen by a particular cooperative member, whose income is tied to the finca’s production. Photograph by Fred Royce. Guest curators Fred Royce and William Messina.

Read more "New incentive-based management system in Cuban citrus"

- UF-IFAS faculty tour Cuban citrus grove

Read more

Read moreUF/IFAS Extension citrus scientist Dr. Steve Futch and UF/IFAS agricultural economist Dr. Tom Spreen (left) were part of a UF delegation that visited the Cuban citrus cooperatives 9 de Abril and 30 de Noviembre in April 2003. Notice the apparent health of these citrus trees before the arrival in Cuba of citrus Huanglongbing (HLB, or citrus greening) disease. An interesting finding from this visit was the comparatively low herbicide use in the Cuban groves: apparently, the presence of a cooperative member in each finca enabled the spot-removal of weeds rather than full-row spraying. Photograph by Fred Royce. Guest curators Fred Royce and William Messina.

- UF-IFAS faculty and students meet with citrus farm workers

Read more

Read moreUniversity of Florida/IFAS faculty and UF students, along with the University of Havana researchers, are hosted at a Cuban citrus farm and meet with farm administrators and workers (2006). This was at the high point of production for Cuba’s citrus industry, when Cuba was the third largest grapefruit producer in the world, behind the United States and Israel. Since that time, Huanglongbing (HLB, or citrus greening) disease has all but wiped out the Cuban citrus industry. HLB also had a very destructive impact on the Florida citrus industry but researchers in Florida and Cuba, and throughout the world, have much to learn from each other on how to try to eliminate or at least control this devastating disease. The individual in the center of the phot in the white shirt is Dr. Jonathan Crane from the UF/IFAS Tropical Research and Education Center in Homestead, Florida. Photograph by Fred Royce. Guest curators Fred Royce and William Messina.

Read more "UF-IFAS faculty and students meet with citrus farm workers"

- UF-IFAS faculty at vegetable farm in central Cuba

Read more

Read moreDistinguished Professor Daniel Cantliffe (left foreground, UF/IFAS Department of Horticultural Science) and other UF/IFAS and University of Havana faculty in the field with administrators and workers at a vegetable farm in central Cuba (2008). Photograph by Fred Royce. Guest curators Fred Royce and William Messina.

Read more "UF-IFAS faculty at vegetable farm in central Cuba"

- Joint UF-University of Havana ‘Our Shared Environment’ workshop in Havana

Read more

Read moreDr. Jorge Angulo, Director of the University of Havana’s Center for Marine Research (Centro de Investigaciones Marinas, CIM-UH) presents a seminar in Havana to University of Florida/IFAS faculty during the UF-UH joint workshop “Our Shared Natural Environment” (2012). Photograph by Fred Royce. Guest curators Fred Royce and William Messina.

Read more "Joint UF-University of Havana ‘Our Shared Environment’ workshop in Havana"

- Cuban research scientists tour citrus packing house in Florida

Read more

Read moreDirector of Cuba’s Plant Health Research Institute (Instituto de Investigaciones de Sanidad Vegetal, INISAV) Dr. Berta Lina Muiño, and fellow INISAV scientists tour the IMG citrus packing house in Vero Beach, Florida in 2015. The collaborative research project between INISAV and the UF/IFAS School of Forest Resources and Conservation (now the UF/IFAS School of Forest, Fisheries, and Geomatics Sciences) was the first USDA-funded project supporting field research in Cuba, and Cuban field research in Florida in nearly 50 years. Photograph by Fred Royce. Guest curators Fred Royce and William Messina

Read more "Cuban research scientists tour citrus packing house in Florida"

- Cuban research scientists at Seald Sweet International

Read more

Read moreUniversity of Florida/IFAS faculty and scientists from Cuba’s Plant Health Research Institute (Instituto de Investigaciones de Sanidad Vegetal, INISAV) meet with representatives from Seald Sweet International to discuss issues and challenges related to safe harvesting, transportation, and distribution of fresh fruits and vegetables (2015). Photograph by Fred Royce. Guest curators Fred Royce and William Messina.

Read more "Cuban research scientists at Seald Sweet International"