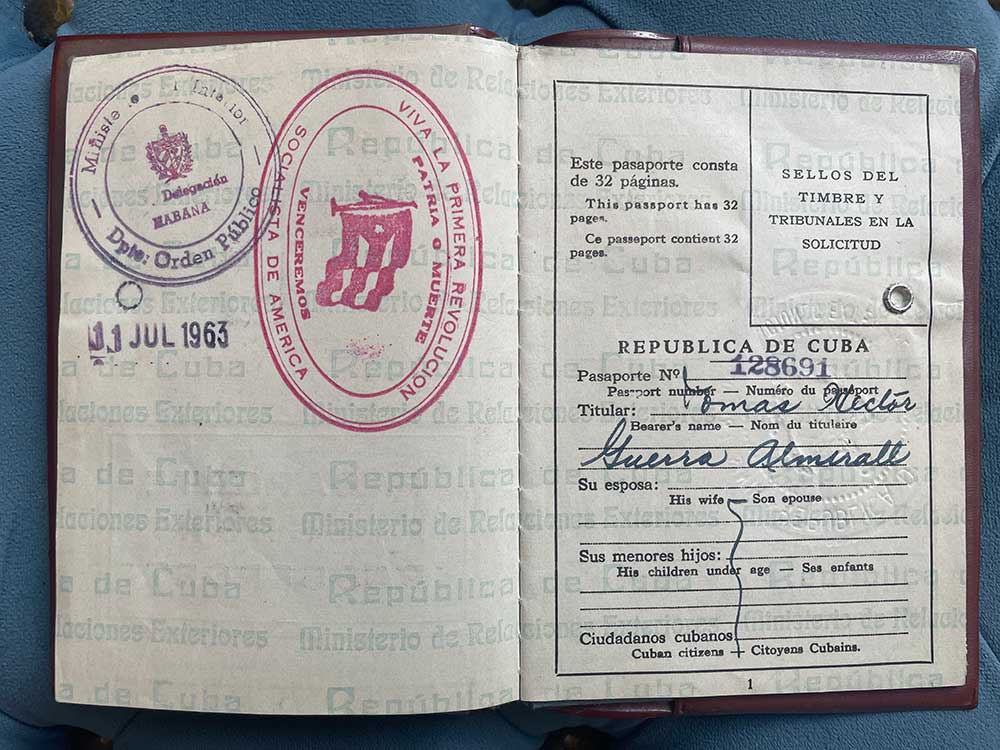

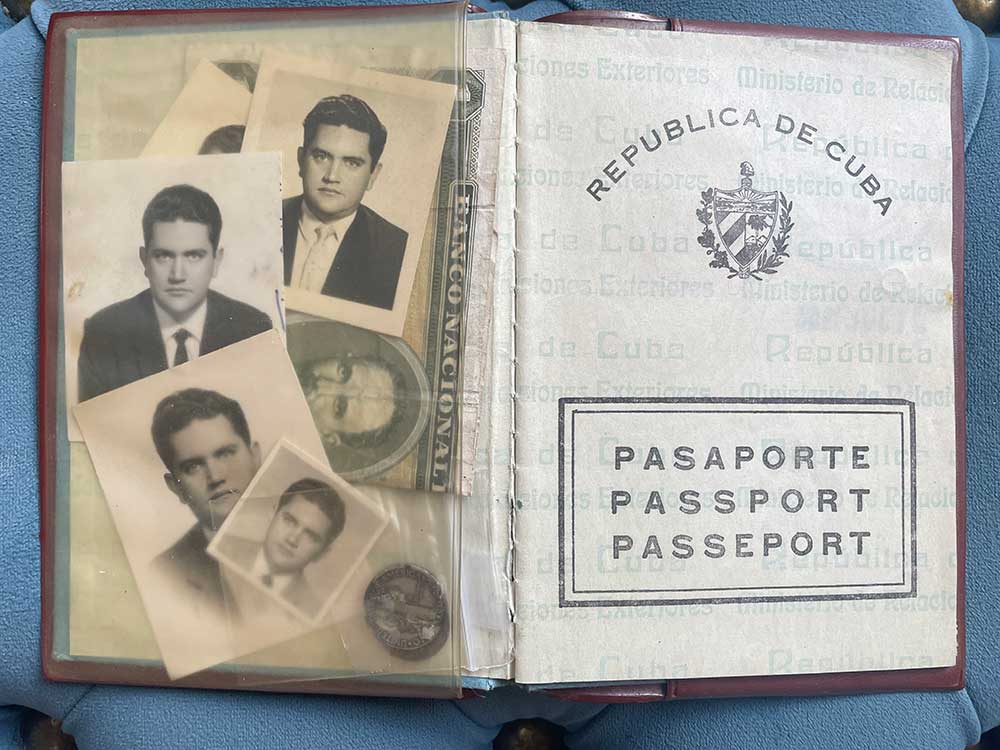

In 1963, my father, Tomás H. Guerra, decided to leave Cuba for exile after the government passed communist reforms that eliminated his peasant family’s right to grow and sell crops independently of the state. Even after he arrived in Spain and, later, New York City, he never threw away the seemingly mundane reminders of how difficult the emotional journey had been. A stamp on the second page reminded him and all others that he was allegedly fleeing his own liberation: “¡Viva la primera Revolución Socialista de América! Patria o muerte. Venceremos” [Long live the first Socialist Revolution of America! Fatherland or Death. We shall triumph]. In the right front pocket, he carried multiple headshots for the many forms he assumed–after filling out so many forms—he would continuously have to complete in order to justify his presence abroad. He also kept the last of the five Cuban pesos that he had in his pocket when he left the island forever. Five pesos was the total amount that 1964-1965 the Cuban government would allow any citizen “abandoning the Revolution” to take with them, along with only a few items of clothes: men were allowed two pairs of pants, three shirts, and one extra set of ropa interior [underwear]. That small list, for both men and women, did not include a coat. When my father arrived in Madrid with my mom on February 4, 1964, and waited outside the airport for a taxi to take them to the Red Cross refugee camp, it was only 35 degrees. Never had they experienced such cold. Personal collection of Lillian Guerra.